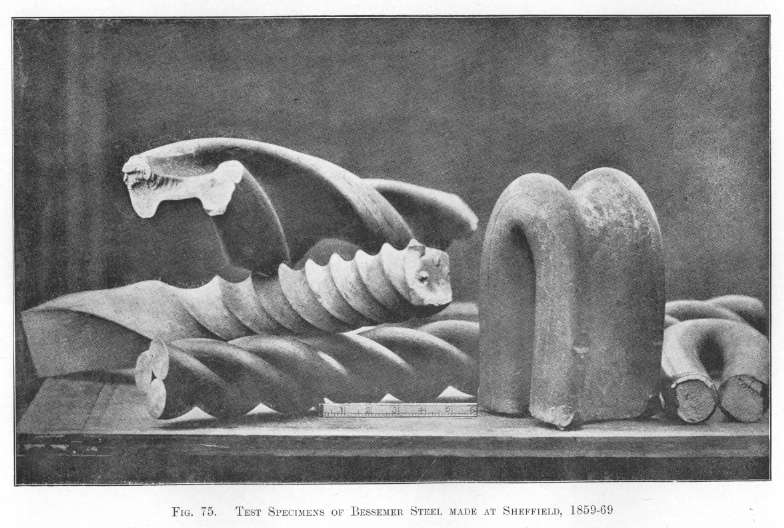

into a vase. As the thin cold steel plate revolves it yields to the pressure exerted upon it by the blunt instrument forced dexterously against it, and by degrees its particles are expanded in some directions and contracted in others, the solid cold steel flowing, like its prototype the potter's clay, and forming almost any variety of circular form which the workman desires to give it. This wondrous change of position of the several parts of the original flat plate takes place without the smallest symptom of a crack or failure at any part of its surface.

These examples demonstrate the marvellous toughness of the Bessemer cast steel when manipulated by a skilful workman.

The small vase on the left, 4 1/2 in. in height and 3 1/2 in. in diameter (Fig. 74, Plate XXXII), is by no means a solitary example. It was one of a group of vases of various forms exhibited by me at the International Exhibition of 1862, that is, thirteen years before Sir Nathaniel Barnaby held up to the public meeting an isolated example of a maltreated plate as a representation of the "treacherous Bessemer steel," which he seemed to think was sufficient to excuse the British Admiralty for their ten years' indifference and apathy. During those ten long years, twenty-four Bessemer steel works had been erected in England alone, having 112 converting vessels with their powerful blast engines, steel-rolling mills, and other expensive plant and buildings, producing annually 700,000 tons of Bessemer steel.

At the time at which I write (1896), when we look into the present state of British shipbuilding, we find that merchant sailing-ships and passenger steam-ships are, in all cases, built of mild cast steel, which is admitted to be the most suitable of known materials for their construction. The way in which mild cast steel (Bessemer and open-hearth) has absolutely superseded iron is proved by the annexed extracts from Lloyds Register of British Shipbuilding for the year 1895.

During 1895, exclusive of war ships, 579 vessels of 950,967 tons gross (viz., 526 steamers of 904,991 tons and 53 sailing vessels of 45,976 tons) have been launched in the United Kingdom. The war ships launched at both Government and private yards amount to 59 of 148,111 tons displacement. The total output of the United Kingdom for the year has, therefore, been 638 vessels of 1,099,078 tons.

As regards the material employed for the construction of the vessels included in the United Kingdom returns for 1895, it is found that, of the steam tonnage, nearly 98.8 per cent. has been built of steel and 1.2 per cent. of iron. The iron steam tonnage is practically made up of trawlers, and comprises no vessel of more than 425 tons. Of the sailing tonnage, 97.0 percent. has been built of steel, and 3.0 per cent. of wood. No iron sailing vessel appears to have been launched during the year.

Can any evidence more clearly show how the opinions of shipbuilders and shipowners, including the great passenger steam-ship owners and the Admiralty itself, have practically condemned iron as a shipbuilding material, with the consequent adoption of mild cast steel in its stead? In considering this evidence it must not be forgotten that mild Bessemer steel has not undergone the smallest alteration in manufacture, or any improvement in quality, since the completion of the eighteen Bessemer steel ships which were built at Liverpool. All that we did then we do now, and consequently the steel was as well adapted for the building of ships at that period as it is at the present day. From 1875 up to 1896 -- that is, a period of twenty years -- the London and North-Western Company have built no less than 4000 Bessemer steel locomotive boilers, and during these twenty years of constant wear and tear, not one of these has ever been treacherous enough to burst. It may further be recorded that the London and North-Western Railway Company made all the Bessemer steel plates used for building their splendid fast Dublin and Holyhead passenger boats, which have so long been in constant use.

Although I have unavoidably used words of censure in speaking of that abstraction, the British Admiralty, no one can doubt that its officials are gentlemen of honour and integrity. They are liable, like the rest of humanity, to errors of judgment, while the traditions of the office, and the conditions under which they work, must tend to develop the conservative side of their character, and render them averse to experiment. But the course they pursue, whether it be technically the wisest or not, represents, I am sure, their honest

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |