on three of its sides, a dotted line indicating where the fourth side is to be sheared; and (3) shows the plate sheared on all four sides. Now, if the Admiralty had ordered every plate delivered to them from the steel-maker to have one side left unsheared, as shown in (2), their own people could have sheared this one side, and cut three pieces, numbered respectively 5, 6, and 7, as marked on the sheared-off piece shown on an enlarged scale at (4). Having done so, the prover would have taken (5) and hammered it into close contact while quite cold, as shown in (8); he might then have taken the piece marked (6), made it red-hot, and while at the proper temperature for working, hammered it into close contact, as shown in (9); these two tests would have proved or disproved the workable quality of the plate, both hot and cold. The piece marked (7) would then have had a 3/4-in. hole punched in it, and a conical steel plug, or "drift," would have been driven into this hole until it was expanded to a given standard size, as shown at (10); this would have proved whether the plate would, or would not, bear punching. Any failure to stand these three usual tests would have justified the return of the plate to the manufacturer, and thus no loss would have been incurred by the Admiralty. With the certainty of perfect safety which these proofs afforded, the London and North-Western Railway Company, acting under the advice of their engineer, and under the responsibility of the directors, did not hesitate to stake the lives of many thousands of persons every day, for whole years together, daily transporting them over hundreds of miles of Bessemer steel rails, over which rolled thousands of Bessemer steel tyres, drawn by hundreds of locomotives having Bessemer steel boilers, steel axles, steel cranks, steel piston-rods, steel guide-bars, steel connecting- rods, etc ., etc. All this went on hourly, weekly, and for years, and had been going on for ten years under the eyes of the British Admiralty and their officials. Mr. Webb and his directors were fully justified in this extensive use of Bessemer steel, for they had carefully and tentatively put it to a long and continuous practical test, and proved to demonstration that no iron made in this country was equal to this Bessemer steel in toughness, strength, and endurance under severe strains.

It would be very instructive to the British taxpayer to know how many hundreds of thousands of pounds were expended by our Admiralty in the construction of iron ships of war during their ten years' abstention from the use of steel, and how much the efficiency of the vessels was reduced by the extra weight involved.

In his paper, Sir Nathaniel Barnaby further stated that the steel shipbuilders at L'Orient scrupulously avoided the use of iron hammers, and that they had various mechanical devices for "coaxing and humouring this material." Why did not the author give the meeting some account of what had been done nearer home? Why did he steer clear of Liverpool, where the material of eighteen steel ships had been shaped and fashioned with steel hammers wielded by the powerful arms of the practised steelsmith, without any coaxing and humouring?" The meeting was also informed that the ordinary steel angles in use at L'Orient cost £27 per ton, and the double-tee bars about £41 per ton; and to this there was to be added the cost of such careful labour as he had described. But private shipbuilders and ship-owners were not deterred by the price of Bessemer steel from using it even ten years before the date at which this paper was written, when Bessemer steel was at least 30 per cent. dearer than in 1875. Would it not have been far better to have quoted the then prices of Bessemer steel in England, instead of giving the absurdly high prices said to obtain in France?

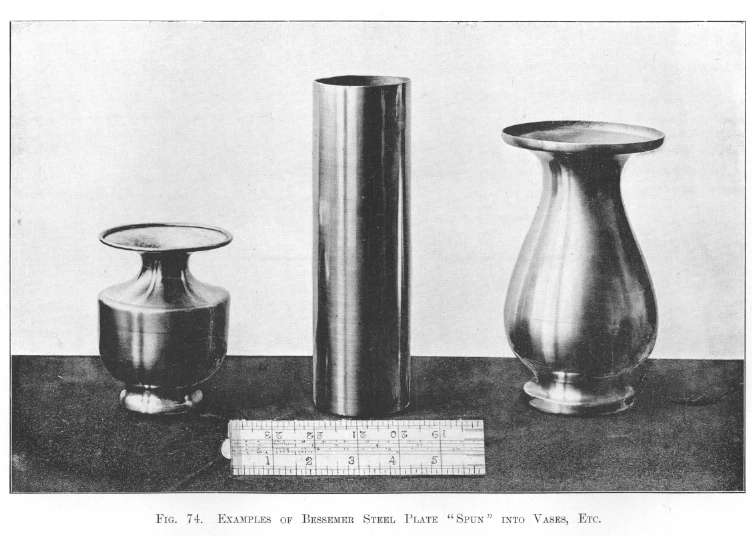

I was present at the reading of Sir Nathaniel Barnaby's paper, when he held up to the meeting the piece of steel plate, which he called "the treacherous Bessemer steel," illustrated in Fig. 72, Plate XXXI. I invite my readers to compare this illustration with the various examples I have had photographed of Bessemer steel tests of gun-forgings (see Figs. 69 and 70, Plates XXVIII. and XXIX.) and with the 11,000 test pieces then accumulated at Crewe. But even more striking than these were the specimens I had prepared thirteen years before. Few would believe, without ocular demonstration, the extraordinary fact that a thin steel plate, 11 in. in diameter and 1/16 in. thick, can be brought without rupture into the forms shown in Fig. 74, Plate XXXII.,

while Fig. 75, Plate XXXIII. shows various pieces of Bessemer steel, of our regular daily manufacture at Sheffield, tested cold. The former are examples of what is called "spinning;" the cold steel plate is made to revolve in a lathe, and is pressed heavily upon by a blunt instrument as it revolves, just as a piece of soft clay revolving on a potter's wheel is pressed upon by his thumb and fingers, and is fashioned

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |