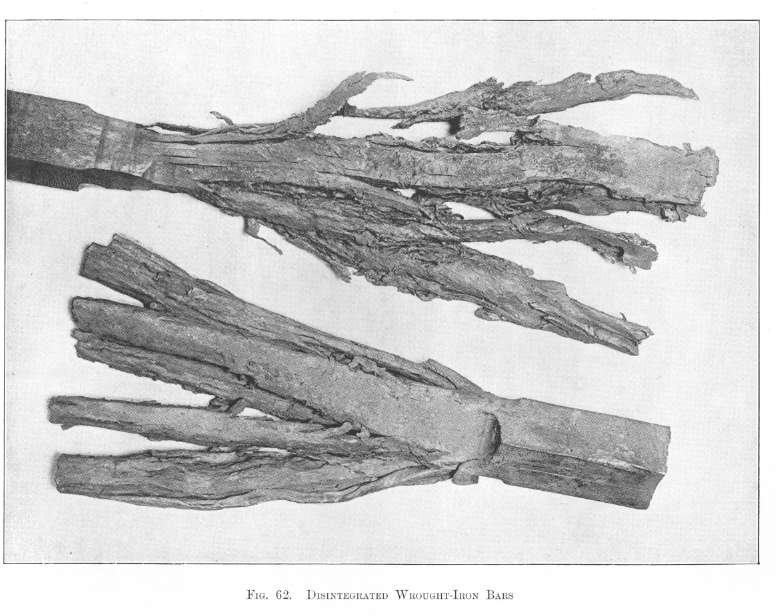

during a short stay at my works at Sheffield, I had the honour of a visit from an active partner in one of the great Yorkshire firms which stand so deservedly high among bar-iron makers. I mentioned this fact of imperfect welding, and the consequent disintegration of bar-iron by simply working it at a temperature below welding heat. My visitor laughed outright at the possibility of such a thing happening to any bar- iron that his firm had ever turned out. I said: "If you will wait while one of my people goes to an iron warehouse in the town and purchases a bar of your iron, I will convince you that I am right." Well, he patiently waited until the bar was procured, and admitted at once that the brand stamped on it was his own. A short length was then cut from it and heated in his presence. It was put under one of the rapidly- moving tilt hammers at that moment being used in forging our bar steel at the same low heat. The result was that the Yorkshire iron bar divided, under this simple treatment, for about a foot of its length into a mass of fibres forming a veritable birch-broom, to the utter astonishment of the manufacturer.

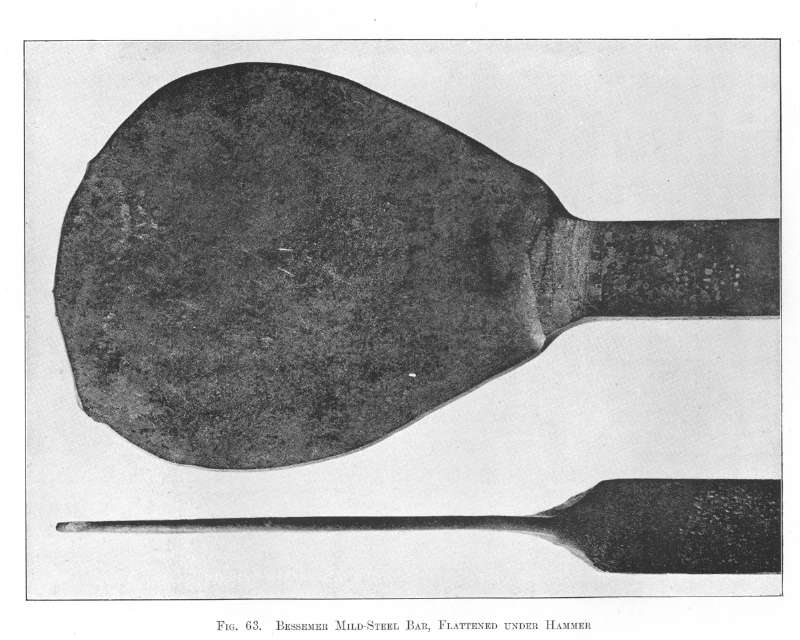

At the time when the two bars of 1-in. square iron, shown in Fig. 62, Plate XXIV., were hammered, a similar bar of Bessemer mild steel was treated at the same temperature under the same hammer. The illustration, Fig. 63, Plate XXV., shows how it simply became extended into a flat undivided surface, without crack or rift in the material.

These examples of forging below a welding heat serve to show the imperfection inevitable in all puddled or welded iron; while the steel example also shows the continuity of parts resulting from the Bessemer steel or homogeneous iron being formed into an ingot while the metal is in a fluid state, hence producing an undivided and indivisible mass, however much it may be hammered, hot or cold.

It will be readily understood how deeply interested I was in the application of my invention to the construction of ordnance, and how much I felt encouraged by the high appreciation of what I had achieved by so competent a person as Colonel Eardley Wilmot. Although I saw that there was an almost endless variety of applications in industry to which this cheap and superior metal could be advantageously applied, I nevertheless felt a strong desire to see it used in the manufacture of guns. Its summary rejection at Woolwich, however, without even a trial, furnished me with yet another proof of the utter foolishness of relying on Government, and made me throw up all idea of following that branch of manufacture as a speciality. With a still lingering desire to put my material to the test of gun-making, I had looked pretty deeply into the subject, in order to see what had already been done by others, and how far the road was still open to me as a gun-manufacturer. On searching at the Patent Office I found the specification of Captain Blakeley, dated February 27th, 1855; in this specification, Captain Blakeley described his invention as consisting of certain improvements in the construction of ordnance, in which an inner tube or cylinder of steel, gun metal, or cast iron, was enclosed in a case or covering of wrought iron or steel, which casing was made in parts, either shrunk on to a cylindrical tube, or forced cold on to a tube, the exterior surface of which was slightly conical, so as, in either case, to tightly grip the inner tube, adding materially to its strength and power of resisting internal pressure. This casing, whether made of cast-iron or steel, might itself be further supported or strengthened by one or more outer layers of rings or hoops, also put on under tension. Here we had clearly and distinctly laid down the vital principles embodied in all modern built-up guns, in this and in other countries -- that of external compression of the inner tube by an outer one; and, unless it can be shown that this patent of Captain Blakeley was anticipated by a prior invention, he must stand before the world as the originator and father of modern built-up artillery. From this patent I saw at once that it would be impossible for me to manufacture built-up guns having an internal steel tube, without direct infringement. Captain Blakeley, at this early period (February, 1855), had the sagacity to see that a steel tube or lining was an indispensible condition of a perfectly built- up gun: not only because of its homogeneous character and freedom from welded joints, and its greater cohesive strength, but also because of its greater hardness and power to resist the severe abrasion of its inner surface, caused by the studs on the projectile moving along the rifled grooves under immense lateral pressure. Although he knew that steel was the best possible material for the lining of the gun, he, nevertheless, thought it prudent to claim also the use of gun-metal and cast-iron, lest he should have his invention evaded by the substitution of either of these last-named homogeneous metals. He, however, evidently thought it unnecessary to guard himself against the possible evasion of his patent built-up gun by the substitution of a welded wrought-iron tube in place of a homogeneous steel one. This doubtless

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |