engrafted on the business I was carrying on; but this one great branch of trade, so earnestly desired had not yet manifested itself. I was accordingly content in the meantime to hold on to everything that fairly paid for the time and capital employed in its production.

My life at this time was pretty much one of hard work and steady attention to business, from which I could only snatch short intervals. Late in the evening I would drop in and have a chat with my father, then advanced in years, but ever anxious to hear of my progress, and desirous to see the latest specimens of Rose engine work, or to discuss with me some of the many new schemes that occupied my thoughts. At that time my two sisters kept house for my father, and in this little family a quiet evening. There was another house, however, to which my steps were involuntarily wont to lead me. My friend, Mr. Richard Alien, had a fair daughter, to whom I had for some time been engaged; thus, between the two families all my leisure hours were spent in friendly intercourse and quiet meetings, without even a desire on my part to mix in any of those gaieties which the world calls Society. Pleasant and delightful as were these evenings, replete with all the charm of unrestricted social amenities, they were, nevertheless, only steps to one great end and aim of all my earthly aspirations: for above all things I desired to exchange my lonely bachelor's apartments for a home of my own. I did not see the wisdom of waiting for an indefinite time on "fickle fortune," so as my betrothed was willing to share my lot in life, we were married. We settled down quietly in Northampton Square, close to my place of business, and I am happy to say that in all the changes and vicissitudes of the sixty-four years that have passed since that happy event, I have never had reason to regret a step which I had taken in the full confidence of youth that I should, in time, be able to carve out for myself a name and a position in the world worthy of her to whom my life was henceforth to be devoted.

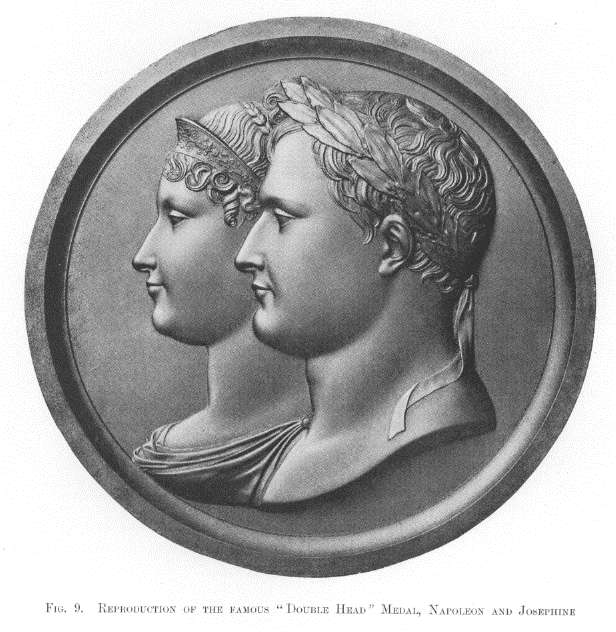

The white metal medallions and casts of natural objects, coated with a film of copper and exhibited by me at the Museum of Arts and Manufactures, in Leicester Square, attracted the attention of a gentleman who had in his possession a great many of the beautiful dies that had been engraved in the French mint, the impressions from which are generally known as the "Napoleon Medals." Some of them were engraved in steel, others were cut in brass, and all were of the most exquisite workmanship. I made arrangements with the owner of these dies to produce a great quantity of bronzed impressions of them at prices which were highly renumerative. For this purpose, I devised a simple apparatus for rapidly stamping the impressions in semi-fluid metal, the only mode by which perfect impressions could be obtained from those dies that were engraved in brass. After some considerable trouble, I produced an alloy of tin and other metals, which differed from the alloy named before in having no zinc in it, though it nevertheless passed so slowly and so gradually from the fluid to the solid state, that the most perfect impressions were obtained with unerring certainty. The shower of splashes inseparable from stamping semifluid metal was received in the case surrounding the dies, and this was automatically closed as the press descended. Immense quantities of these fine medallions were made, and beautifully bronzed without impairing their sharpness. I still possess a few of them, more or less damaged by time; and as an example of their general character, I give photographic reproductions of some of them in the figures on Plates V. and VI., each being the same size as the original. Those I have selected include the famous "double- head," Napoleon and Josephine Fig. 9, Plate V.), said to be the finest portrait medals of the Emperor ever produced.

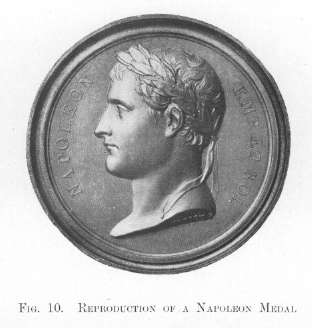

Fig. 10, Plate VI., is another of these Napoleon medals,

and Fig. 11 is a medallion of the head of Minerva.

One day I was called upon by a gentleman, a Mr. James Young, who presented a card of introduction from a barrister to whom I was well known. His object was to obtain the assistance of a mechanician to devise, or construct, a machine for setting up printing type. I had a long and pleasant conversation with this most agreeable client; indeed, our frequent meetings and friendly discussions resulted in a close friendship, terminating only with his death, which occurred several years later. My friend Young, who was a silk merchant at Lille, had persuaded himself that by playing on keys, arranged somewhat after the style of a pianoforte, all the letters required in a printed page could be mechanically arranged in

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |