“But, my dear boy, there are other states of society than monarchy; we have republics and despotisms.”

“We have, but how long do they last compared to the first? There is a cycle in the changes which never varies. A monarchy may be overthrown by a revolution, and republicanism succeed, but that is shortly followed by despotism, till, after a time, monarchy succeeds again by unanimous consent, as the most legitimate and equitable form of government; but in none of these do you find a single advance to equality. In a republic, those who govern are more powerful than the rulers in a restricted monarchy— a president is greater than a king, and next to a despot, whose will is law. Even in small societies you find that some will naturally take the lead and assume domination. We commence the system at school, when we are first thrown into society, and there we are taught systems of petty tyranny. There are some few points in which we can obtain equality in this world, and that equality can only be obtained under a well-regulated form of society, and consists in an equal administration of justice and of laws to which we have agreed to submit for the benefit of the whole— the equal right to live and not be permitted to starve, which has been obtained in this country. And when we are all called to account, we shall have equal justice. Now, my dear father, you have my opinion.”

“Yes, my dear, this is all very well in the abstract; but how does it work?”

“It works well. The luxury, the pampered state, the idleness— if you please, the wickedness of the rich, all contribute to the support, the comfort, and employment of the poor. You may behold extravagance— it is a vice; but that very extravagance circulates money, and the vice of one contributes to the happiness of many. The only vice which is not redeemed by producing commensurate good, is avarice. If all were equal there would be no arts, no manufactures, no industry, no employment. As it is, the inequality of the distribution of wealth may be compared to the heart, pouring forth the blood like a steam-engine through the human frame, the same blood returning from the extremities by the veins, to be again propelled, and keep up a healthy and vigorous circulation.”

“Bravo, Jack!” said Dr. Middleton. “Have you anything to reply, sir?” continued he, addressing Mr. Easy.

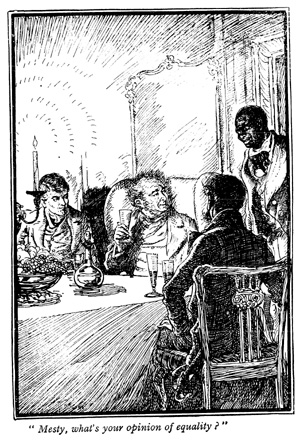

“To reply, sir?” replied Mr. Easy with scorn, “why, he has not given me half an argument yet— why, that black servant even laughs at him— look at him there showing his teeth. Can he forget the horrors of slavery? can he forget the base unfeeling lash?— no, sir, he has suffered, and he can estimate the divine right of equality. Ask him now, ask him if you dare, Jack, whether he will admit the truth of your argument.”

“Well, I’ll ask him,” replied Jack, “and I tell you candidly that he was once one of your disciples. Mesty, what’s your opinion of equality?”

“Equality, Massa Easy?” replied Mesty, pulling up his cravat; “I say d— n equality, now I major domo.”

“The rascal deserves to be a slave all his life.”

“True, I ab been slave— but I a prince in my own country— Massa Easy tell how many skulls I have.”

“Skulls— skulls— do you know anything of the sublime science; are you a phrenologist?”

“I know man’s skull very well in Ashantee country, anyhow.”

“Then if you know that, you must be one. I had no idea that the science had extended so far— maybe it was brought from thence. I will have some talk with you to-morrow. This is very curious, Dr. Middleton, is it not?”

“Very, indeed, Mr. Easy.”

“I shall feel his head to-morrow after breakfast, and if there is anything wrong I shall correct it with my machine. By-the-bye, I have quite forgot, gentlemen; you will excuse me, but I wish to see what the carpenter

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |