What a change from the morning of the day before!—but twenty-four hours had passed away, and the sea had been smooth, the frigate dashed through the blue water, proud in all her canvas, graceful as a swan. Since that, there had been fire, tempest, lightning, disaster, danger, and death; her masts were tossed about on the snowy waves hundreds of miles away from her—and she, a wreck, was rolling heavily, groaning and complaining in every timber as she urged her impetuous race with the furious running sea.

How wrong are those on shore who assert that sailors are not religious!—how is it possible, supposing them to be possessed of feeling, to be otherwise? On shore, where you have nothing but the change of seasons, each in his own peculiar beauty—nothing but the blessings of the earth, its fruit, its flowers—nothing but the bounty, the comforts, the luxuries which have been invented, where you can rise in the morning in peace, and lay down your head at night in security—God may be neglected and forgotten for a long time; but at sea, when each gale is a warning, each disaster acts as a check, each escape as a homily upon the forbearance of Providence, that man must be indeed brutalized who does not feel that God is there. On shore we seldom view him but in all his beauty and kindness; but at sea we are as often reminded how terrible he is in his wrath. Can it be supposed that the occurrences of the last twenty-four hours were lost upon the minds of any one man in that ship? No, no. In their courage and activity they might appear reckless, but in their hearts they acknowledged and bowed unto their God.

Before the day was over, a jury-foremast had been got up, and sail having been put upon it, the ship was steered with greater ease and safety—the main brace had been spliced to cheer up the exhausted crew, and the hammocks were piped down.

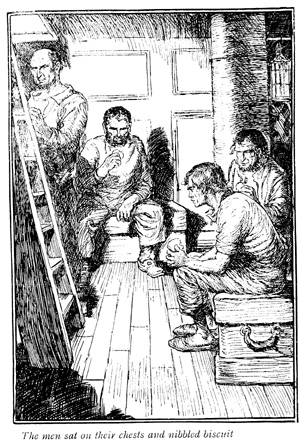

As Gascoigne had observed, some of the men were not very much pleased to find that they were minus their blankets, but Captain Wilson ordered their losses to be supplied by the purser and expended by the master; this quite altered the case, as they obtained new blankets in most cases for old ones, but still it was impossible to light the galley fire, and the men sat on their chests and nibbled biscuit. By twelve o’clock that night the gale broke, and more sail was necessarily put on the scudding vessel, for the sea still ran fast and mountains high. At daylight the sun burst out and shone brightly on them, the sea went gradually down, the fire was lighted, and Mr. Pottyfar, whose hands were again in his pockets, at twelve o’clock gave the welcome order to pipe to dinner. As soon as the men had eaten their dinner, the frigate was once more brought to the wind, her jury-mast forward improved upon, and more sail made upon it. The next morning there was nothing of the gale left except the dire effects which it had produced, the black and riven stump of the foremast still holding up a terrific warning of the power and fury of the elements.

Three days more, and the Aurora joined the Toulon fleet. When she was first seen it was imagined by those on board of the other ships that she had been in action; they soon learnt that the conflict had been against more direful weapons than any yet invented by mortal hands. Captain Wilson waited upon the admiral, and of course received immediate orders to repair to port and refit. In a few hours the Aurora had shaped her course for Malta, and by sunset the Toulon fleet were no longer in sight.

“By de holy poker, Massa Easy, but that terrible sort of gale the other day anyhow—I tink one time, we all go to Davy Joney’s lacker.”

“Very true, Mesty; I hope never to meet with such another.”

“Den, Massa Easy, why you go to sea? When man ab no money, noting to eat, den he go to sea; but everybody say you ab plenty money—why you come to sea?”

“I’m sure I don’t know,” replied Jack thoughtfully; “I came to sea on account of equality and the rights of man.”

“Eh, Massa Easy, you come to wrong place anyhow; now I tink a good deal lately, and by all de power, I tink equality all stuff.”

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |