Captain Wilson looked significantly at Mr. Sawbridge.

“I certainly did hoffer my political opinions, Captain Vilson; but you must be avare that ve hall ’ave an hequal stake in the country—and it’s a Hinglishman’s birthright.”

“I’m not aware what your stake in the country may be, Mr. Easthupp,” observed Captain Wilson, “but I think that, if you used such expressions, Mr. Easy was fully warranted in telling you his opinion.”

“I ham villing, Captain Vilson, to make hany hallowance for the ’eat of political discussion—but that is not hall that I ’ave to complain hof. Mr. Heasy thought proper to say that I was a swindler and a liar.”

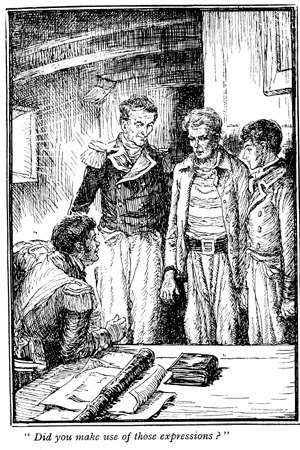

“Did you make use of those expressions, Mr. Easy?”

“Yes, sir, he did,” continued the steward, “and, moreover, told me not to cheat the men, and not to cheat my master the purser. Now, Captain Vilson, is it not true that I am in a wery hostensible sitevation, but I flatter myself that I ’ave been vell edecated, and vos wonce moving in a wery different society—misfortains vill ’appin to us hall, and I feel my character has been severely injured by such impertations;” whereupon Mr. Easthupp took out his handkerchief, flourished, and blew his nose. “I told Mr. Heasy, that I considered myself quite as much of a gentleman as himself, and at hall hewents did not keep company with a black feller (Mr. Heasy will understand the insinevation), vereupon Mr. Heasy, as I before said, your vorship, I mean you, Captain Vilson, thought proper to kick me down the ’atchvay.”

“Very well, steward, I have heard your complaint, and now you may go.”

Mr. Easthupp took his hat off with an air, made his bow, and went down the main ladder.

“Mr. Easy,” said Captain Wilson, “you must be aware, that by the regulations of the service by which we are all equally bound, it is not permitted that any officer shall take the law into his own hands. Now, although I do not consider it necessary to make any remark as to your calling the man a radical blackguard, for I consider his impertinent intrusion of his opinions deserved it, still you have no right to attack any man’s character without grounds—and as that man is in an office of trust, you were not at all warranted in asserting that he was a cheat. Will you explain to me why you made use of such language?”

Now our hero had no proofs against the man; he had nothing to offer in extenuation, until he recollected, all at once, the reason assigned by the captain for the language used by Mr. Sawbridge. Jack had the wit to perceive that it would hit home, so he replied, very quietly and respectfully,—

“If you please, Captain Wilson, that was all zeal.”

“Zeal, Mr. Easy? I think it but a bad excuse. But pray, then, why did you kick the man down the hatchway?—you must have known that that was contrary to the rules of the service.”

“Yes, sir,” replied Jack, demurely, “but that was all zeal, too.”

“Then allow me to say,” replied Captain Wilson, biting his lips, “that I think that your zeal has in this instance been very much misplaced, and I trust you will not show so much again.”

“And yet, sir,” replied Jack, aware that he was giving the captain a hard hit, and therefore looked proportionally humble, “we should do nothing in the service without it—and I trust one day, as you told me, to become a very zealous officer.”

“I trust so, too, Mr. Easy,” replied the captain. “There, you may go now, and let me hear no more of kicking people down the hatchway. That sort of zeal is misplaced.”

“More than my foot was, at all events,” muttered Jack, as he walked off.

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |