real power of mind. Although slow, what he learnt he invariably retained. This lad’s name was Gossett. His father was a wealthy yeoman of Lynn, in Norfolk. There were at the time but three other midshipmen in the ship, of whom it can only be said that they were like midshipmen in general, with little appetite for learning, but good appetites for dinner, hating everything like work, fond of everything like fun, fighting à outrance one minute, and sworn friends the next—with general principles of honour and justice, but which were occasionally warped according to circumstances; with all the virtues and vices so heterogeneously jumbled and heaped together, that it was almost impossible to ascribe any action to its true motive, and to ascertain to what point their vice was softened down into almost a virtue, and their virtues from mere excess degenerated into vice. Their names were O’Connor, Mills, and Gascoigne. The other shipmates of our hero it will be better to introduce as they appear on the stage.

After Jack had dined in the cabin he followed his messmates Jolliffe and Gascoigne down into the midshipmen’s berth.

“I say, Easy,” observed Gascoigne, “you are a devilish free and easy sort of a fellow, to tell the captain that you considered yourself as great a man as he was.”

“I beg your pardon,” replied Jack, “I did not argue individually, but generally, upon the principles of the rights of man.”

“Well,” replied Gascoigne, “it’s the first time I ever heard a middy do such a bold thing; take care your rights of man don’t get you in the wrong box—there’s no arguing on board of a man—of—war. The captain took it amazingly easy, but you’d better not broach that subject too often.”

“Gascoigne gives you very good advice, Mr. Easy,” observed Jolliffe; “allowing that your ideas are correct, which it appears to me they are not, or at least impossible to be acted upon, there is such a thing as prudence, and however much this question may be canvassed on shore, in his majesty’s service it is not only dangerous in itself, but will be very prejudicial to you.”

“Man is a free agent,” replied Easy.

“I’ll be shot if a midshipman is,” replied Gascoigne, laughing, “and that you’ll soon find.”

“And yet it was the expectation of finding that equality that I was induced to come to sea.”

“On the first of April, I presume,” replied Gascoigne. “But are you really serious?”

Hereupon Jack entered into a long argument, to which Jolliffe and Gascoigne listened without interruption, and Mesty with admiration: at the end of it, Gascoigne laughed heartily and Jolliffe sighed.

“From whence did you learn all this?” inquired Jolliffe.

“From my father, who is a great philosopher, and has constantly upheld these opinions.”

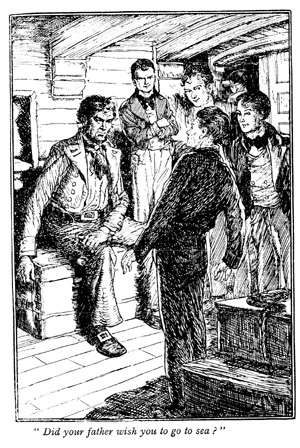

“And did your father wish you to go to sea?”

“No, he was opposed to it,” replied Jack, “but of course he could not combat my rights and freewill.”

“Mr. Easy, as a friend,” replied Jolliffe, “I request that you would as much as possible keep your opinions to yourself: I shall have an opportunity of talking to you on the subject, and will then explain to you my reasons.”

As soon as Mr. Jolliffe had ceased, down came Mr. Vigors and O’Connor, who had heard the news of Jack’s heresy.

“You do not know Mr. Vigors and Mr. O’Connor,” said Jolliffe to Easy.

| Previous chapter/page | Back | Home | Email this | Search | Discuss | Bookmark | Next chapter/page |